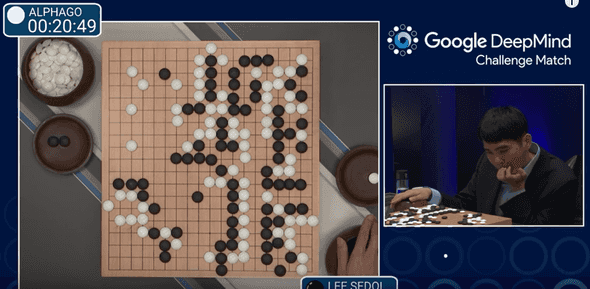

After Lee Sedol—currently the second best-ranked Go player in the world—was defeated by Google’s AlphaGo AI in March 2016, there was a roar in the AI community as it was commonly believed that it would take at least another decade for an AI program to achieve such a feat.

To get an idea of why this was a common belief among AI researchers, it is useful to understand how traditional chess programs work (a game where AIs have vastly surpassed humans), and then see why the same approach couldn’t be used for the game of Go.

Chess Engine: A Simulation Approach

In chess, an algorithm known as minimax is commonly used to write chess programs (also known as chess engines) that play the game at grandmaster levels. The most sophisticated of these programs use this approach at their core, including popular open source programs such as Stockfish.

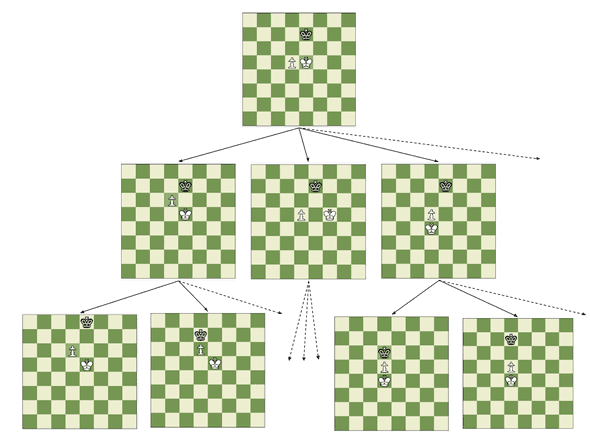

Minimax, which performs what is known as a “game tree search,” can be explained in simple terms as a simulation of the game that takes into account all possible moves of one player and all counter moves of the opponent, until either the end of the game is reached or a certain predefined number of moves has been simulated (more on this later). In essence, it’s a way of simulating all possible futures of a game from a current position, and then figuring out which of the best futures can be forced by the player in turn (assuming perfect play by both sides) to get the best possible outcome.

Determining who has an advantage at any given moment—and is therefore more likely to win the game—is another crucial component of this approach and, in fact, of basically any approach to building a chess engine. The piece of the chess engine that does this is called a static evaluation function. It isn’t necessary to evaluate every possible position in a game tree, only those that appear at the “bottom” (those which represent game situations far enough into the future.)

In practice, this simulation approach cannot be carried out for all possibles moves in a game. To see why, consider that the average number of legal moves at any point in the game is approximately 30. That means that, the further we want to look into the future, the bigger the number of game positions we need to evaluate, growing at an exponential pace. To get an idea of the magnitude of this growth, consider how a naive approach that looks at every single ending of the game and simulates the game to number of moves would have to evaluate roughly positions. An average game in chess lasts about moves, so this number would amount to the astronomically large !

So how does a chess engine manage to play the game without considering such a huge number of positions? Well, for starters, rather than evaluating all terminal nodes of a theoretical game tree, most chess engines establish a limit on the maximum number of moves they will simulate for each possible future of the game. This prunes the simulation space significantly, but requires an evaluation function that can estimate with high accuracy which player would be more likely to win the game if they were to continue playing until the end, assuming perfect play on each side. Some other clever tricks are often used to reduce the number of positions to be evaluated in the simulation. The most common and famous one is called alpha-beta pruning. In the end, however, they all align with the same basic idea of minimax, they just happen to be very clever ways of avoiding the simulation of parts of the game tree that don’t contribute any new information.

AlphaGo: Simulation + Learning + Self-Play

Back to the reason why AI researchers thought it would take much longer for a Go engine to beat a world champion, it basically has to do with the average number of moves that can be played in a given Go position. In chess, this number—known as the ramification factor of the game tree—is 30, but in Go it is around 300, making it completely infeasible to use the same approach that chess engines use to play a good game, even with all the tricks known to reduce the simulation space.

Despite its apparent simplicity, Go is actually a more complex game than chess and often requires humans to use their intuition to make the right moves. This posed a very difficult challenge for researchers, who had to turn to other techniques, such as Monte Carlo Tree Search (MTSC)—an approach conceptually similar to minimax, but which relies on randomness and the classical exploration/exploitation tradeoff—to try and overcome the problem, but their success was quite limited using this approach alone (the best Go engines before AlphaGo only managed to beat amateur players.)

One of the key insights that the team behind AlphaGo had was:

What if instead of exploring random moves using MCTS, we explored moves that a strong Go player would play in a given position?

Fortunately, the existence of thousands of recorded games between master Go players and the rise of sophisticated supervised machine learning algorithms made this insight actionable.

Using that data, they were able to train a couple of deep learning models (convolutional neural networks, or CNNs) that could predict, given a Go position, which moves were most likely to be made by an expert human player. The model was not perfect (all models are wrong but some are more useful than others), but it predicted some of the best moves, so it was a huge help in pruning the simulation space. A simpler form of this approach had been tried in the past with several other games, but only limited success had been achieved, mostly due to the lack of good data and the right neural network architecture.

They also added a second neural network that acted as an evaluation function and served to limit the depth of simulation, in an attempt to increase the speed with which Monte Carlo tree search converged to an optimal value.

It’s worth noting that the first of these models alone was so powerful that it actually defeated all prior Go engines, but it wasn’t good enough to reach the level of professional Go players. To get there, the authors had to figure out a clever combination of those deep learning models and a variation of Monte Carlo tree search that gave AlphaGo the power to defeat one of the best human Go players in a very conclusive manner.

There are other important nitty-gritty details that explain how they managed to make AlphaGo such a good player (hint: reinforcement learning and self-play), but that’s probably the topic for another post.

Conclusion

To be fair, the version of AlphaGo that defeated Lee Sedol was a distributed program running on multiple computers using a large amount of resources, but it’s still impressive that the amount of computing power it needed was much lower than that used by IBM’s DeepBlue in the historical 1996 match against chess world champion Gary Kasparov.

This is a very impressive demonstration of how the combination of multiple techniques in AI (classical search techniques in game trees + supervised machine learning + reinforcement learning) can bring about incredible results that were once thought to be much harder to achieve.

With its ability to learn from others (the supervised learning part) and even from itself (the reinforcement learning part), AlphaGo opens up an interesting door into the possibilities of creating complex computer systems that evolve and improve their performance, just as we humans do.

Further Reading

-

📝 AlphaGo. Wikipedia provides a more technical high-level description of AlphaGo, and links to many other articles that explain it in even more detail.

-

🌐 AlphaGo Official. This is the official page of the team behind AlphaGo: DeepMind.

-

📝 AlphaGo: Technical Overview. This is a detailed technical overview of how AlphaGo works. If you’re looking to understand the nitty-gritty details, this is a good place to get started.